Designing an Online Learning Component

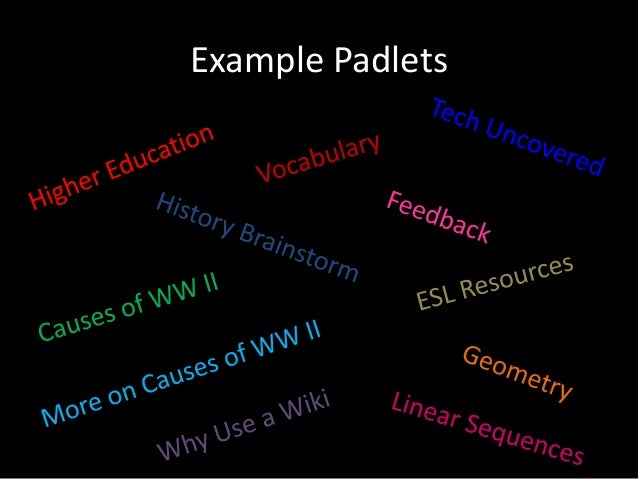

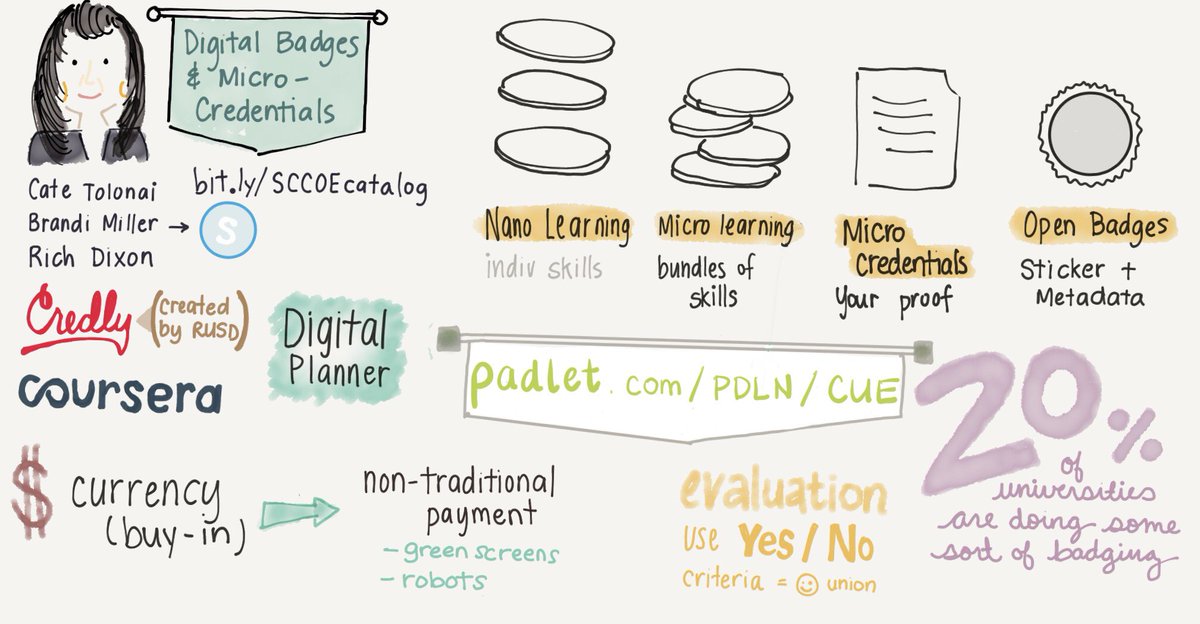

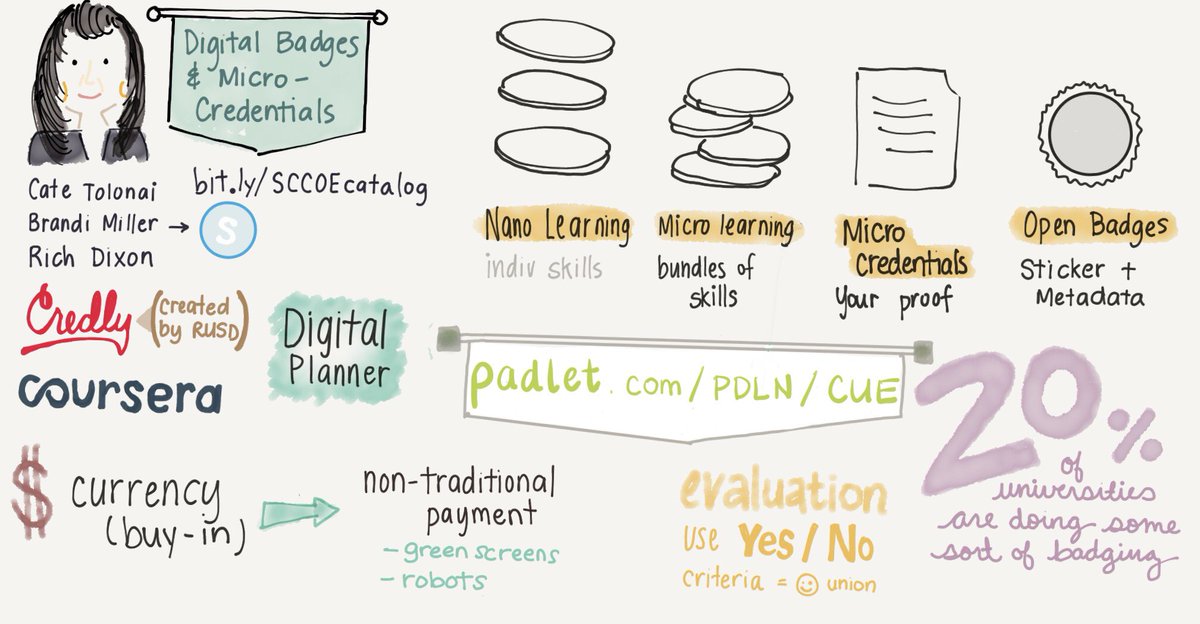

One of the tools of web 2.0 that can help when carrying out collaborative and cooperative activities is Padlet, it allows us to abandon, at some moments of the school action, the master class and adopt methodologies in which the student Participates much more like active agent of its learning.

Padlet starts from a very simple idea, proposes a blank wall. You can register what you want there and where you want it; Is a collaborative tool where teachers and students can work at the same time and in the same work environment.

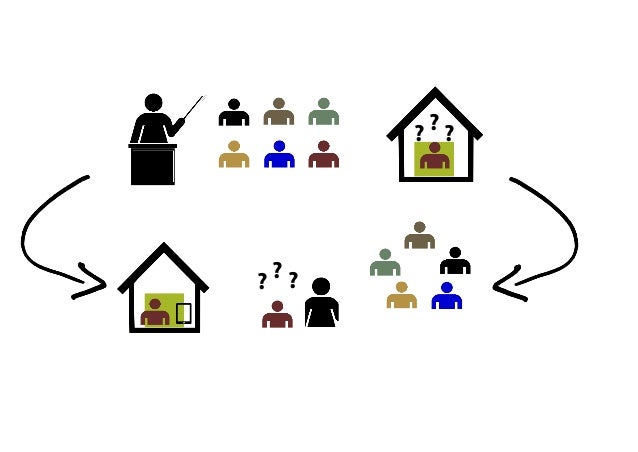

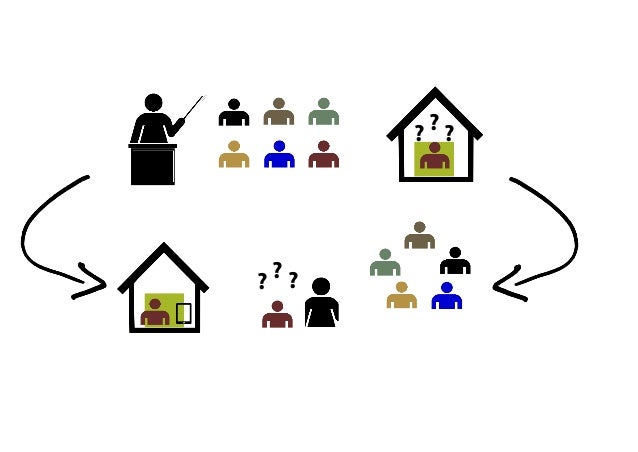

The tool can be very effective for the project work in the process of active listening by the teacher, also for the resolution of questions or questions launched by the students (if we are already taking steps to the so-called inverted class or flipped classroom, we can Propose that the questions or doubts that arise to the student can be put on the wall, so that the next day, or when applicable, can be resolved by the class).

The resources put on the wall can go from elements that we have published in the network (Google Drive, videos of youtube) as documents that we have stored in our PC or device and that we can upload to the repository of Padlet.

The role of the teacher in an interactive classroom, using the PADLET program, means entering a different dimension of education.

The role of the teacher in an interactive classroom, using the PADLET program, means entering a different dimension of education.

3. A discussion of the strategies you have chose to engage your students with the online assessment, activity, or resource with supporting evidence. See Module 7: Engaging and Motivating Students for strategies (400 words if you choose the written submission format or 4 minute recording if you choose to submit a video format).

3. A discussion of the strategies you have chose to engage your students with the online assessment, activity, or resource with supporting evidence. See Module 7: Engaging and Motivating Students for strategies (400 words if you choose the written submission format or 4 minute recording if you choose to submit a video format).

In relation to New Technologies this implies that the teacher must know them in all its dimensions, be able to analyze them critically, to make an adequate selection of both the technological resources and the information that they carry and must be able to use them and perform a Adequate curricular integration in the classroom.

In relation to New Technologies this implies that the teacher must know them in all its dimensions, be able to analyze them critically, to make an adequate selection of both the technological resources and the information that they carry and must be able to use them and perform a Adequate curricular integration in the classroom.

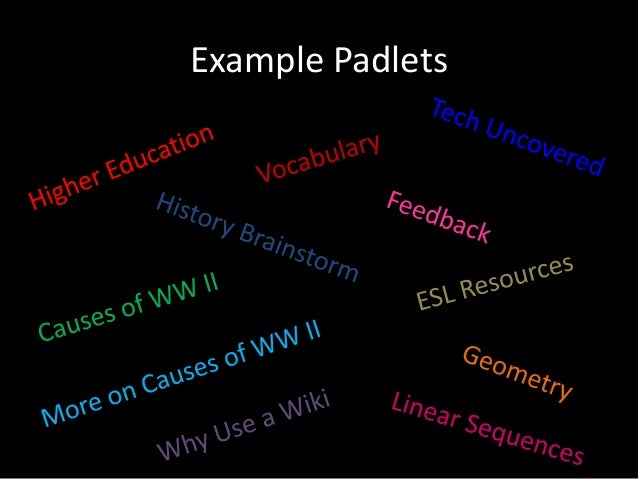

We can affirm then that the New Technologies affect the profile of the teacher to the extent that they demand more training for their use and an open and flexible attitude to the changes that occur in society as a consequence of technological progress.Brainstorming or brainstrorming. Why do not we force students to ask their own questions? For example, if we are going to study rivers, what information from a river can be useful for everyday life? The tool can be very effective for work by projects in the process of active listening by the teacher (define the subject of the project, what we already know, what we want to learn, what has been learned. ..).

We can affirm then that the New Technologies affect the profile of the teacher to the extent that they demand more training for their use and an open and flexible attitude to the changes that occur in society as a consequence of technological progress.Brainstorming or brainstrorming. Why do not we force students to ask their own questions? For example, if we are going to study rivers, what information from a river can be useful for everyday life? The tool can be very effective for work by projects in the process of active listening by the teacher (define the subject of the project, what we already know, what we want to learn, what has been learned. ..).

Gathering sources of information for a research work: When studying a specific teaching unit, we can ask our students to compile sources of information. This requires that the teacher has previously taught them to search the internet; So we teach students to differentiate sources that are reliable from those that are not and to have a certain critical spirit with the information they "consume".

Gathering sources of information for a research work: When studying a specific teaching unit, we can ask our students to compile sources of information. This requires that the teacher has previously taught them to search the internet; So we teach students to differentiate sources that are reliable from those that are not and to have a certain critical spirit with the information they "consume".

The resources can go from elements that we have published in the network (google drive, videos of youtube ...) like documents that we have stored in our PC or device and that we can upload to the repository of padlet.

The resources can go from elements that we have published in the network (google drive, videos of youtube ...) like documents that we have stored in our PC or device and that we can upload to the repository of padlet.

Beyond the technical conditions of construction of the measuring instruments, it is evident that the overall quality of an educational system, a school or a particular teacher can not be judged from the standardized test results, which Definition and application limitations are usually restricted to the measurement of specific content and skills (usually in mathematics, language, and sometimes science) in some cohorts, and therefore can not account for the complexity of educational outcomes, much less Of the conditions in which they occur.

Beyond the technical conditions of construction of the measuring instruments, it is evident that the overall quality of an educational system, a school or a particular teacher can not be judged from the standardized test results, which Definition and application limitations are usually restricted to the measurement of specific content and skills (usually in mathematics, language, and sometimes science) in some cohorts, and therefore can not account for the complexity of educational outcomes, much less Of the conditions in which they occur.

It is evaluated to learn, not to apply prizes and punishments. The evaluation in education must always be formative, and therefore, provide data and elements of judgment that support the decision making in favor of quality.

It is evaluated to learn, not to apply prizes and punishments. The evaluation in education must always be formative, and therefore, provide data and elements of judgment that support the decision making in favor of quality.

A description of the online activity, assessment or resource including specifics about what the students and the teacher would have to do. For example, how would the student interact with it? What role does the teacher play in facilitating the technology? You can do this in writing or you can draw diagrams, create a slide show, an interactive flowchart, or use open technologies to build your working example. Make sure whatever method you use, that it can be accessed by your colleagues who will peer-assess your work (500 words if you choose the written submission format or 5 minute recording if you choose to submit a video format)..

Practice – Learning through practice enables the learner to adapt their actions to the task goal, and use the feedback to improve their next action. Feedback may come from self-reflection, from peers, from the teacher, or from the activity itself, if it shows them how to improve the result of their action in relation to the goal

Practice – Learning through practice enables the learner to adapt their actions to the task goal, and use the feedback to improve their next action. Feedback may come from self-reflection, from peers, from the teacher, or from the activity itself, if it shows them how to improve the result of their action in relation to the goal

Academic Writing:

Educative technology

http://www.oei.es/historico/oeivirt/tecnologiaeducativa.htm

11. Baker, D. B.,

J. T. Fouts, C. A. Gratama, J. N. Clay, and S. G. Scott. 2006. Digital

Learning Commons: High school seniors’ online course taking patterns in

Washington State. Seattle: Fouts and Associates.http://www.learningcommons.org.

11. Baker, D. B.,

J. T. Fouts, C. A. Gratama, J. N. Clay, and S. G. Scott. 2006. Digital

Learning Commons: High school seniors’ online course taking patterns in

Washington State. Seattle: Fouts and Associates.http://www.learningcommons.org. 15. Bennett, R. E.,

H. Persky, A. Weiss, and F. Jenkins. 2007. Problem solving in technology rich

environments: A report from the NAEP Technology-based Assessment Project,

Research and Development Series (NCES 2007-466). U.S.

Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Washington,

DC.

15. Bennett, R. E.,

H. Persky, A. Weiss, and F. Jenkins. 2007. Problem solving in technology rich

environments: A report from the NAEP Technology-based Assessment Project,

Research and Development Series (NCES 2007-466). U.S.

Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Washington,

DC. 22.

Bridgeland, J., J. Dilulio, and K. Morrison. 2006 (March). The

silent epidemic: Perspectives of high school dropouts.Washington,

DC: Civic Enterprises, LLC, and Peter D. Hart Research Associates for the Bill

& Melinda Gates Foundation. http://www.civicenterprises.net/pdfs/thesilentepidemic3-06.pdf.

22.

Bridgeland, J., J. Dilulio, and K. Morrison. 2006 (March). The

silent epidemic: Perspectives of high school dropouts.Washington,

DC: Civic Enterprises, LLC, and Peter D. Hart Research Associates for the Bill

& Melinda Gates Foundation. http://www.civicenterprises.net/pdfs/thesilentepidemic3-06.pdf. 29.

CoSN (Consortium for School Networking). 2009. Mastering

the moment: A guide to technology leadership in the economic crisis.http://www.cosn.org/Initiatives/MasteringtheMoment/MasteringtheMomentHome/tabid/4967/Default.aspx.

29.

CoSN (Consortium for School Networking). 2009. Mastering

the moment: A guide to technology leadership in the economic crisis.http://www.cosn.org/Initiatives/MasteringtheMoment/MasteringtheMomentHome/tabid/4967/Default.aspx. 31. Darling-Hammond,

L. 2010. The

flat world and education. New York: Teachers College Press.

31. Darling-Hammond,

L. 2010. The

flat world and education. New York: Teachers College Press. 41.

Graham, S. 2009. Students in rural schools have limited access

to advanced mathematics courses. Durham, NH: Carsey Institute, University of

New Hampshire.

41.

Graham, S. 2009. Students in rural schools have limited access

to advanced mathematics courses. Durham, NH: Carsey Institute, University of

New Hampshire. 51. Johnson, L., A.

Levine, R. Smith, and S. Stone. 2010. The 2010 horizon report. Austin, TX: The

New Media Consortium.

51. Johnson, L., A.

Levine, R. Smith, and S. Stone. 2010. The 2010 horizon report. Austin, TX: The

New Media Consortium. 57.

Ladson-Billings, G. 2009. The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers

of African American children. San Francisco: Wiley.

57.

Ladson-Billings, G. 2009. The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers

of African American children. San Francisco: Wiley. 66.

Minstrell, J., and P. Kraus. 2005. Guided inquiry in the science

classroom. In How people learn: History, mathematics, and science in the

classroom, ed. M. S. Donovan and J. D. Bransford, 475–12. Washington, DC:

National Academies Press.

66.

Minstrell, J., and P. Kraus. 2005. Guided inquiry in the science

classroom. In How people learn: History, mathematics, and science in the

classroom, ed. M. S. Donovan and J. D. Bransford, 475–12. Washington, DC:

National Academies Press. 79.

National Research Council. 2000. How people learn: Mind, brain,

experience, and school. Eds. J. D. Bransford, A. Brown, and R. Cocking.

Washington, DC: National

79.

National Research Council. 2000. How people learn: Mind, brain,

experience, and school. Eds. J. D. Bransford, A. Brown, and R. Cocking.

Washington, DC: National 85.

National Science Foundation. 2008a. Beyond being there: A

blueprint for advancing the design, development, and evaluation of virtual

organizations. Final report from Workshops on Building Virtual Organizations.

Arlington, VA: NSF.

85.

National Science Foundation. 2008a. Beyond being there: A

blueprint for advancing the design, development, and evaluation of virtual

organizations. Final report from Workshops on Building Virtual Organizations.

Arlington, VA: NSF. 94.

Pellegrino, J. W., N. Chudowsky, and R. Glaser, eds. 2001.

Knowing what students know: The science and design of educational assessment.

Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

94.

Pellegrino, J. W., N. Chudowsky, and R. Glaser, eds. 2001.

Knowing what students know: The science and design of educational assessment.

Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

104.

Richardson, V., and R. S. Kile. 1999. Learning from videocases.

In Who learns what from cases and how? The research base for teaching and

learning with cases, ed. M. A. Lundeberg, B. B. Levin, and H. L. Harrington,

121–136. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

104.

Richardson, V., and R. S. Kile. 1999. Learning from videocases.

In Who learns what from cases and how? The research base for teaching and

learning with cases, ed. M. A. Lundeberg, B. B. Levin, and H. L. Harrington,

121–136. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. 114.

Squire, L. R., C. E. L. Stark, and R. E. Clark. 2004. The medial

temporal lobe. Annual Review of Neuroscience 27:279–306.

114.

Squire, L. R., C. E. L. Stark, and R. E. Clark. 2004. The medial

temporal lobe. Annual Review of Neuroscience 27:279–306. 116.

Strudler, N., and D. Hearrington. 2009. Quality support for ICT

in schools. In International handbook of information technology in primary and

secondary education, ed. J. Voogt and G. Knezek, 579–596. New York: Springer.

116.

Strudler, N., and D. Hearrington. 2009. Quality support for ICT

in schools. In International handbook of information technology in primary and

secondary education, ed. J. Voogt and G. Knezek, 579–596. New York: Springer.

126.

Vendlinski, T., and R. Stevens. 2002. Assessing student

problem-solving skills with complex computer-based tasks. Journal of Technology,

Learning, and Assessment 1 (3). http://www.jtla.org.

126.

Vendlinski, T., and R. Stevens. 2002. Assessing student

problem-solving skills with complex computer-based tasks. Journal of Technology,

Learning, and Assessment 1 (3). http://www.jtla.org.

Instructions

Your task is to design and describe the online component for your own class that you identified in Assignment 1. You do not have to actually build a working example of your online component in your chosen technology – but if your design uses an open technology that your peer reviewers can access, we encourage you to do so - just be mindful of any privacy or access issues as explored in Module 2: Open and institutionally supported technologies. You can present a written description, flowcharts, screen designs, video screen captures etc - anything that you think communicates your design clearly. Watch a video overview of what we expect in Assignment 2 here.

Assignment Questions

Drawing upon the concepts explored in the course, the case studies presented, resources, activities, and discussions include responses to the following in this final culminating assessment:

- A description of the online activity, assessment or resource including specifics about what the students and the teacher would have to do. For example, how would the student interact with it? What role does the teacher play in facilitating the technology? You can do this in writing or you can draw diagrams, create a slide show, an interactive flowchart, or use open technologies to build your working example. Make sure whatever method you use, that it can be accessed by your colleagues who will peer-assess your work (500 words if you choose the written submission format or 5 minute recording if you choose to submit a video format).

Padlet

One of the tools of web 2.0 that can help when carrying out collaborative and cooperative activities is Padlet, it allows us to abandon, at some moments of the school action, the master class and adopt methodologies in which the student Participates much more like active agent of its learning.

Padlet starts from a very simple idea, proposes a blank wall. You can register what you want there and where you want it; Is a collaborative tool where teachers and students can work at the same time and in the same work environment.

The tool can be very effective for the project work in the process of active listening by the teacher, also for the resolution of questions or questions launched by the students (if we are already taking steps to the so-called inverted class or flipped classroom, we can Propose that the questions or doubts that arise to the student can be put on the wall, so that the next day, or when applicable, can be resolved by the class).

The resources put on the wall can go from elements that we have published in the network (Google Drive, videos of youtube) as documents that we have stored in our PC or device and that we can upload to the repository of Padlet.

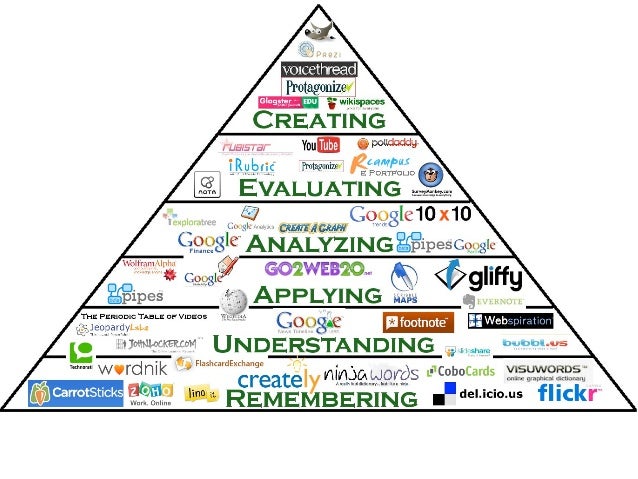

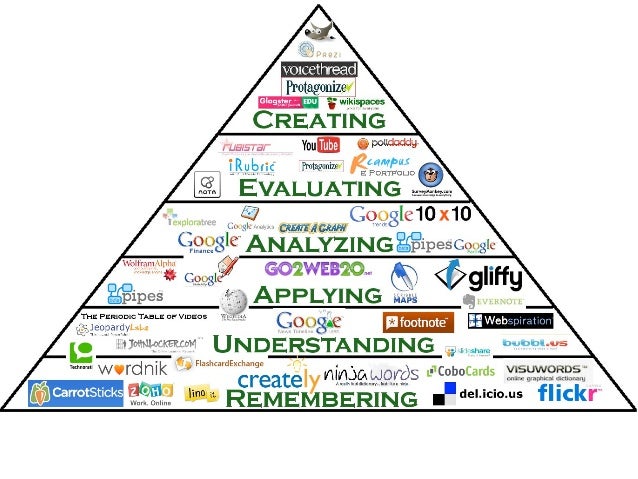

You can achieve the highest goals of the Bloom Learning Pyramid. Thus, if I can create, evaluate, apply, analyze, synthesize (a knowledge through a document created through Padlet), it is inferred that, through this seemingly simple tool, one can in a collaborative way stimulate in a simple way Fun alternative way for meaningful learning.

The role of the teacher in an interactive classroom, using the PADLET program, means entering a different dimension of education.

Within the center, the role of the teacher has changed. Or you must. Their role is different and must adapt to new realities. In this sense, four positions have been defined in its work:

1. Mediator to guide the process of transmission of information that must be transformed to be useful.

2. Facilitator of the development of the abilities of the student: this must be his own educator and the teacher to help him achieve it.

3. Impulse of the adaptation to the changes, helping the student.

4. Content finder or recommender within the enormous information transfer that can be found both on the network and outside it.

2.A description of how the online activity, assessment, or resource is aligned with the rest of the curriculum in your course. See Module 3: Planning Online Learning for strategies for curriculum alignment (200 words if you choose the written submission format or 2 minute recording if you choose to submit a video format).

Characteristics of PADLET as an educational tool

Gratuitous:

Accessible:

Intuitive:

Malleable:

Encourage collaboration

Encourages communication

Linkable, through links, texts, videos

Encourages creativity

Encourages the synthesis of the central ideas (mental map) of a theme

Playful environment

All these characteristics allow it to be a powerful educational weapon, which will enhance the educational activities programmed.

You can achieve the highest goals of the Bloom Learning Pyramid. Thus, if I can create, evaluate, apply, analyze, synthesize (a knowledge through a document created through Padlet), it is inferred that, through this seemingly simple tool, one can in a collaborative way stimulate in a simple way Fun alternative way for meaningful learning.

There are many reasons to use the New Technologies in the teaching-learning process, among them we can mention:

- Allows the student to be part and involved in the learning process, becoming an active subject rather than mere spectator.

- Eliminates many discipline problems in the classroom. When the student engages in work, there is less time for conflict.

- Students become protagonists. They are empowered to seek answers to their questions, making the learning process much more interesting for them.

- The teacher becomes a guide and help, which produces rapprochement with the students.

- Reduce work to the teacher in relation to paper, texts .

- Its use allows the students to make the subsequent change, school-work, school-university, be smoother, in the sense that they will be very familiar with the technology, used today in any professional field you can imagine.

- The exchange of information through the network, makes it easier and faster than ever before.

The role of the family is determinant to create a strong link between family-society-school and the situation of the student within that relationship. In this sense, four relevant points have emerged:

1. The new educator family should be: active, global, open, with an integral, participatory, internally and externally connected view, and develop and foster critical thinking.

2. Relationships within families: it is imperative that the child is the interest of the family and parents help in the process of their education.

3. The family-school relationship: make aware that the whole society is responsible for the education of young people. Generate a climate of trust in all levels.

4. Families learn. Virtual reality breaks the school and home walls and the new information environments in which young people move are accessible to the family and must know how to use and analyze them critically. Enable spaces in which all agents can teach and learn

The presence of New Technologies in society and the potential that these offer as resources for education are a sufficient reason to justify their impact on the profile of the teacher, insofar as it has to develop its educational action in a coherent way With the society in which it lives taking full advantage of the resources it offers.

Resolution of questions or questions asked by the students: If we are already taking steps to the so-called inverted class or flipped classroom, we can propose that the questions or doubts that arise to the student can be placed on the wall, so that the next day, or When applicable, can be resolved by the class.

Synthesize the most important ideas of a topic. The wall can be used so that each student takes in a space bounded by the teacher the five or ten most important ideas of a topic.

Nor should we forget that it can be a tool used by the teacher to:

Compilation of resources to use in the classroom for a specific didactic unit.

4.A plan for evaluating your online assessment, activity, or resource to determine its effectiveness. See Module 8: Evaluation Strategies for strategies (400 words if you choose the written submission format or 4 minute recording if you choose to submit a video format).

. Evaluate the work done by students. Since the environment allows it, establishing a certain nomenclature in the creation of the wall, can be used so that the teacher can make comments, guide the students or evaluate the work done by them.

Measuring educational outcomes in schools and school systems has often become a problem for education authorities around the world. The creation of rankings, and the use of results to qualify good or bad schools, good or bad teachers and even the progress of the country regarding educational quality, has given a warning about the true scope and limitations of the Measuring programs.

Beyond the technical conditions of construction of the measuring instruments, it is evident that the overall quality of an educational system, a school or a particular teacher can not be judged from the standardized test results, which Definition and application limitations are usually restricted to the measurement of specific content and skills (usually in mathematics, language, and sometimes science) in some cohorts, and therefore can not account for the complexity of educational outcomes, much less Of the conditions in which they occur.

Beyond the technical conditions of construction of the measuring instruments, it is evident that the overall quality of an educational system, a school or a particular teacher can not be judged from the standardized test results, which Definition and application limitations are usually restricted to the measurement of specific content and skills (usually in mathematics, language, and sometimes science) in some cohorts, and therefore can not account for the complexity of educational outcomes, much less Of the conditions in which they occur.

Evaluation in education is never an isolated judgment on the final impact of a process, but is fundamentally an input. Educational evaluation aims to provide feedback on educational progress, so that those who must make decisions, in the classroom, the school or the educational system, have solid evidence to support the actions to be taken.

It is evaluated to learn, not to apply prizes and punishments. The evaluation in education must always be formative, and therefore, provide data and elements of judgment that support the decision making in favor of quality.

It is evaluated to learn, not to apply prizes and punishments. The evaluation in education must always be formative, and therefore, provide data and elements of judgment that support the decision making in favor of quality.

That each actor has the appropriate information for the decisions to be made at their level should be a key requirement of the educational evaluation systems. What would be useful to know a score or a result, if your analysis does not allow you to know what is being done right and wrong, what are the spaces where there should be improvements. This implies that authorities, school administrators, teachers, students and families should have access to relevant information in the results, in order to support their decisions and their responsibilities, and above all, to strengthen the joint work among all actors to introduce the Changes that are necessary.

Activity 1:

Examine question types and questioning strategies and apply to own teaching

context Identify the need for constructive feedback as a vehicle for effective

learning and links between feedback and motivation, quality and inclusivity

issues. Email this to your tutor.

Self- and

Peer-assessment

- Increases

student involvement and motivation if done in a supportive environment

- Increase

amount and dimensions of feedback

- Creates

greater awareness of how assessment criteria and marks are achieved

- Is

formative assessment in itself

- Both

will probably need a tutor-produced proforma to guide activity

- The different educational dimensions are not yet sufficiently articulated, both in the consideration of their design and in the call and evaluation of their forjadores. This brings a stand by that contradicts the very essence of progress in each of these areas separately. Several aspects then need to be considered, analyzed and redesigned not only to not block the advances but to clear the multiple paths that open to us to be covered. The management areas belonging to institutional structures, both those made up of teaching staff and non-teaching professionals, related to the design and evaluation of activities, must be internalized from the vastness of integrative activities that teachers address. They must know to what extent these activities cover their respective specialties but also are projected through the universe of new technologies. The courses of professional development that are permanently programmed in educational institutions for the teaching plant must be adapted and given also in management, executive, administrative, organizational, evaluating. The institutionalization of this formative "routine" will surely provide a more approximate dimension of what really means the study, preparation, research and creativity that requires the approach of educational technology in all its channels: virtual education, tele-education, Multimedia, online courses, videoprograms, etc., etc. The use of technological resources should be optimized, understanding that in the fantastic fact of overcoming temporal space limitations, traditional teaching-learning processes are enriched and new paths of education are projected and multiplied. The areas responsible for technological innovations in educational institutions must establish a horizontal communication with the evaluation bodies of the teaching activity. Why? Because it is necessary to avoid these disparities between areas that must inevitably coexist, interact, and feed back. Arriving at the end of these observations, reflections, conclusions and proposals, we can say that the best thing, to all this, is that beyond advances and shortcomings, beyond fantasies and realities, beyond horizons and paradoxes, we are still in a Experimental phase in the use of new technologies incorporated to the learning environments. This allows us, fortunately, to reflect and propose new alternatives, to exchange and grow.My presentation

Send your homework

A description of the online activity, assessment or resource including specifics about what the students and the teacher would have to do. For example, how would the student interact with it? What role does the teacher play in facilitating the technology? You can do this in writing or you can draw diagrams, create a slide show, an interactive flowchart, or use open technologies to build your working example. Make sure whatever method you use, that it can be accessed by your colleagues who will peer-assess your work (500 words if you choose the written submission format or 5 minute recording if you choose to submit a video format)..

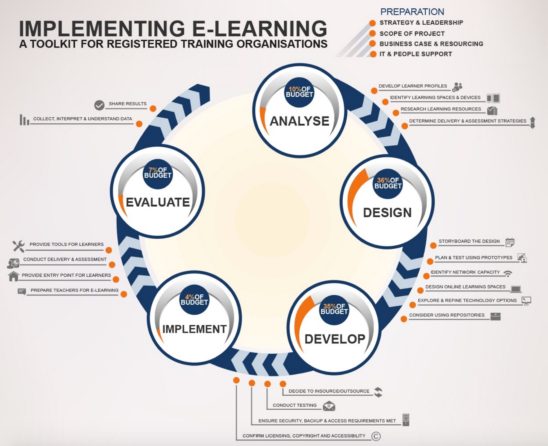

E-learning tools

Acquisition – Learning through acquisition is what learners are doing when they are listening to a lecture or podcast, reading from books or websites, and watching demos or videos

| Conventional Method | Digital Technology |

|---|---|

| Multimedia websites, digital documents, y interactive content |

Collaboration – Learning through collaboration embraces mainly discussion, practice, and production. Building on investigations and acquisition it is about taking part in the process of knowledge building itself

| Conventional Method | Digital Technology |

|---|---|

|

|

Discussion – Learning through discussion requires the learner to articulate their ideas and questions, and to challenge and respond to the ideas and questions from the teacher, and/or from their peers.

| Conventional Method | Digital Technology |

|---|---|

|

email discussions

Web-conferencing tools

|

Investigation – Learning through investigation guides the learner to explore, compare and critique the texts, documents and resources that reflect the concepts and ideas being taught.

| Conventional Method | Digital Technology |

|---|---|

| Online advice and guidance

Using digital tools to search for information

|

Practice – Learning through practice enables the learner to adapt their actions to the task goal, and use the feedback to improve their next action. Feedback may come from self-reflection, from peers, from the teacher, or from the activity itself, if it shows them how to improve the result of their action in relation to the goal

Practice – Learning through practice enables the learner to adapt their actions to the task goal, and use the feedback to improve their next action. Feedback may come from self-reflection, from peers, from the teacher, or from the activity itself, if it shows them how to improve the result of their action in relation to the goal| Conventional Method | Digital Technology |

|---|---|

| Using models |

Production – Learning through production is the way the teacher motivates the learner to consolidate what they have learned by articulating their current conceptual understanding and how they used it in practice

| Conventional Method | Digital Technology |

|---|---|

| Digital documents |

eLearning hosting systems and Learning Management Systems (LMS)

Authoring Tools

More web tools that do not need learners to register:

Describe how the online activity, assessment, or resource is aligned with the rest of the curriculum in your course. See Module 3: Planning Online Learning for strategies for curriculum alignment (200 words if you choose the written submission format or 2 minute recording if you choose to submit a video format).

Discuss the strategies you have chosen to engage your students with the online assessment, activity, or resource with supporting evidence. See Module 7: Engaging and Motivating Students for strategies (400 words if you choose the written submission format or 4 minute recording if you choose to submit a video format).

A plan for evaluating your online assessment, activity, or resource to determine its effectiveness. See Module 8: Evaluation Strategies for strategies (400 words if you choose the written submission format or 4 minute recording if you choose to submit a video format).

We can work within the learning objectives and examination structure to develop a 21st Century Pedagogy.

Make use of:

- Student blogs

- Social media for communication (allowing learners to create their own back channel)

- Allow students to be producers of material (showcase digitally)

- Encourage team work and collaboration, with clearly defined roles and individual objectives

- Create scenarios to allow learners to explore situations in a safe environment, rewarded through elements of game mechanics.

Make students part of the curriculum development process “design for partnership” approach that can be incorporated, as an underlying pedagogical approach to facilitate the creation of meaningful learning experiences in a technology-enhanced teaching and learning environment (liezel, 2017).

References:

Adams, S. (2014). La parte superior 10 habilidades que los empleadores quieren en la mayoría 2015 graduados [en línea]. https://www.forbes.com/sites/susanadams/2014/11/12/the-10-skills-employers-most-want-in-2015-graduates/#3909ade02511 [1 marzo 2017]

Edutopia (2015) 10 Los sellos de 21st Century Enseñanza y Aprendizaje [en línea]. https://www.edutopia.org/discussion/10-hallmarks-21st-century-teaching-and-learning [1 marzo 2017]

McLoughlin, C. y Lee, M.J.W. 2007. El software social de aprendizaje andparticipatory: opciones pedagógicas con technologyaffordances en la Web 2.0 era. TIC: Ofrecer opciones forLearners y Aprendizaje: Actas Ascilite Singapore2007, páginas. 664-675. www.ascilite.org.au/conferences/singapore07/procs/mcloughlin.pdf [7 July 2016].

Mitra, S. (2013). Build a school in the cloud (online video). TEDConference 2013. https://www.ted.com/talks/sugata_mitra_build_a_school_in_the_cloud#t-17380 [1 marzo 2017]

Leadbeater, C. and Wong, A. 2010. Learning from the Extremes:A White Paper. San Jose, Calif., Cisco Systems Inc. www.cisco.com/web/about/citizenship/socio-economic/docs/Learning fromExtremes_WhitePaper.pdf (Accessed 24 May2014).

liezel, N. (2017). Students as collaborators in creating meaningful learning experiences in technology-enhanced classrooms. British Journal of Educational Technology. Early veiw online.

EE.UU. (2016) Internet access – hogares y las personas: 2016 [en línea] https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/householdcharacteristics/homeinternetandsocialmediausage/bulletins/internetaccesshouseholdsandindividuals/2016#mobile-or-smartphones-are-the-most-popular-devices-used-by-adults-to-access-the-internet [1 marzo 2017]

Robinson, K. (2006). ¿Cómo las escuelas matan la creatividad (online video). TEDConference 2006. Monterey, California. www.ted.com/talks/ken_robinson_says_scholos_kill_creativity [1 marzo 2017].

Saavedra, A. y las víctimas, V. 2012. La enseñanza y el aprendizaje de habilidades 21stcentury: Lecciones de las Ciencias del Aprendizaje. Informe AGlobal Ciudades Red de Educación. New York, AsiaSociety. http://asiasociety.org/~~V el / rand-0512REPORT.pdf [8 July 2016].

la UNESCO (2015). El futuro del aprendizaje 3: ¿Qué tipo de pedagogías para el siglo 21? [en línea] http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002431/243126e.pdf [1 marzo 2017]

Interactive Options in Online Learning

Teaching, Learning and Assessment - Richard Nelson Online

Engaging students with Padlet, View your Grade Centre by Tutor Group and New Group Peer Assessment tool

Formative and Summative Interpretations of Assessment Information

John Hattie

School of Education

The University of Auckland

Auckland, New Zealand

General Teaching and Learning

Academic Writing:

E-learning:

& Nbsp;

Pocket Books (a great quick reference):

Creative Teaching Pocketbook

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Educative technology

http://www.oei.es/historico/oeivirt/tecnologiaeducativa.htm

1.

Richey, R. C., Silber, K. H., & Ely,

D. P. (2008). Reflections on the 2008 AECT Definitions of the Field. TechTrends,

52(1), 24-25.

2.

Ely, D.P. (1963). The changing role

of the audiovisual process in education: A definition and a glossary of related

terms. TCP Monograph No. 1. AV Communication Review, 11(1). Supplement No:6.

3.

Association for Educational

Communications and Technology. (1972). The field of educational technology: a

statement of definition. Audio-visual Instruction, 17(8), 36-43.

4.

Association for Educational

Communications and Technology (1977). The definition of educational technology.

Washington, D.C.: Association for Educational Communications and Technology.

5.

Seels, B. B., & Richey, R. C.

(1994). Instructional technology: The definition and domains of the field.

Washington, DC: Association for Educational Communications and Technology.

6.

The Encyclopedia

of Educational Technology. What is Educational Technology? Retrieved

from: http://www.etc.edu.cn/eet/eet/articles/edtech/index.htm

7.

Spector, J. M. (2015). Foundations of

educational technology: Integrative approaches and interdisciplinary

perspectives. Routledge.

8.

Hsu, Y. C., Hung, J. L., & Ching,

Y. H. (2013). Trends of educational technology research: More than a decade of

international research in six SSCI-indexed refereed journals. Educational

Technology Research and Development, 61(4), 685-705.

9.

Davies, I. K., & Schwen, T. M.

(1972). Toward a Definition of Instructional Development.

10.

Ancess, J. 2000. The reciprocal influence of teacher learning,

teaching practice, school restructuring, and student learning outcomes. Teachers

College Record 102 (3): 590–619.

12. Balfanz, R.,

and N. Legters. 2004. Locating the dropout crisis: Which high

schools produce the nation’s dropouts? Where are they located? Who attends

them? Baltimore: Center for Research on the Education of

Students Placed At-Risk, Johns Hopkins University. http://www.csos.jhu.edu/crespar/techReports/Report70.pdf.

13. Banks, J., K.

Au, A. Ball, P. Bell, E. Gordon, K. Gutiérrez, S. Heath, C. Lee, Y. Lee, J.

Mahiri, N Nasir, G. Valdés, and M. Zhou. 2006. Learning in and out of school in diverse

environments: Life-long, life-wide, life-deep. Seattle: NSF

LIFE Center and University of Washington Center for Multicultural Education.

14.

Barron, B. 2006. Interest and self-sustained learning as

catalysts of development: A learning ecology perspective.Human Development 49 (4):

153–224.

15. Bennett, R. E.,

H. Persky, A. Weiss, and F. Jenkins. 2007. Problem solving in technology rich

environments: A report from the NAEP Technology-based Assessment Project,

Research and Development Series (NCES 2007-466). U.S.

Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Washington,

DC.

15. Bennett, R. E.,

H. Persky, A. Weiss, and F. Jenkins. 2007. Problem solving in technology rich

environments: A report from the NAEP Technology-based Assessment Project,

Research and Development Series (NCES 2007-466). U.S.

Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Washington,

DC.

16.Berry, A. M.,

and S. E. Wintle. 2009. Using laptops to facilitate middle school

science learning: The results of hard fun. Gorham, ME: Maine

Education Policy Research Institute.

17. Black, P., and

D. Wiliam. 1998. Inside the black box: Raising standards

through classroom assessment. London: King’s College.

18. Black, S. E.,

and L. M. Lynch. 2003. The new economy and the organization of work. In The

handbook of the new economy, ed. D.C. Jones. New York: Academic

Press.

19.Borko, H., V.

Mayfield, S. Marion, R. Flexer, and K. Cumbo. 1997. Teachers’ developing ideas

and practices about mathematics performance assessment: Successes, stumbling

blocks, and implications for professional development.Teaching and Teacher Education 13

(3): 259–278.

20.

Bound, J., M. Lovenheim, and S. Turner. 2009. Why have

college completion rates declined? An analysis of changing student preparation

and collegiate resources. Working Paper 15566, National Bureau

of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

21. Bransford, J.

D., B. Barron, R. Pea, A. Meltzoff, P. Kuhl, P. Bell, R. Stevens, D. Schwartz,

N. Vye, B. Reeves, J. Roschelle, and N. Sabelli. 2006. Foundations and

opportunities for an interdisciplinary science of learning. InCambridge

handbook of the learning sciences, ed. K. Sawyer, 19–34. New York:

Cambridge University Press.

22.

Bridgeland, J., J. Dilulio, and K. Morrison. 2006 (March). The

silent epidemic: Perspectives of high school dropouts.Washington,

DC: Civic Enterprises, LLC, and Peter D. Hart Research Associates for the Bill

& Melinda Gates Foundation. http://www.civicenterprises.net/pdfs/thesilentepidemic3-06.pdf.

22.

Bridgeland, J., J. Dilulio, and K. Morrison. 2006 (March). The

silent epidemic: Perspectives of high school dropouts.Washington,

DC: Civic Enterprises, LLC, and Peter D. Hart Research Associates for the Bill

& Melinda Gates Foundation. http://www.civicenterprises.net/pdfs/thesilentepidemic3-06.pdf.

23.

Brown, J. S., and R. P. Adler. 2008. Minds on fire: Open

education, the long tail, and learning 2.0. Educause Review:17–32.

24.

Brown, W. E., M. Lovett, D. M. Bajzek, and J. M. Burnette. 2006.

Improving the feedback cycle to improve learning in introductory biology: Using

the Digital Dashboard. In Proceedings of World Conference on E-Learning

in Corporate, Government, Healthcare, and Higher Education, ed. G.

Richards, 1030–1035. Chesapeake, VA: AACE.

25.

Brynjolfsson, E., and L. M. Hitt. 1998. Beyond the productivity

paradox: Computers are the catalyst for bigger changes. Communications

of the ACM 41 (8): 49-55.

26.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2007. Table 1: The 30 fastest

growing occupations covered in the 2008–2009 Occupational Outlook Handbook. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/ooh.t01.htm.

27.

Childress, S. M., D. P. Doyle, and D. A. Thomas. 2009. Leading

for equity: The pursuit of excellence in Montgomery County Public Schools. Cambridge:

Harvard Education Press.

28.

Collins, A., and R. Halverson. 2009. Rethinking education in the age of technology:

The digital revolution and schooling in America. New York:

Teachers College Press.

29.

CoSN (Consortium for School Networking). 2009. Mastering

the moment: A guide to technology leadership in the economic crisis.http://www.cosn.org/Initiatives/MasteringtheMoment/MasteringtheMomentHome/tabid/4967/Default.aspx.

29.

CoSN (Consortium for School Networking). 2009. Mastering

the moment: A guide to technology leadership in the economic crisis.http://www.cosn.org/Initiatives/MasteringtheMoment/MasteringtheMomentHome/tabid/4967/Default.aspx.

30.

Campuzano, L., M. Dynarski, R. Agodini, and K. Rall. 2009. Effectiveness

of reading and mathematics software products: Findings from two student cohorts (NCEE

2009-4041). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and

Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of

Education.

32.

Dede, C. 2009. Immersive interfaces for engagement and learning. Science 323:

66–69.

33.

Dieterle, E. 2009. Neomillennial learning styles and River City. Children,

Youth and Environments 19 (1): 245–278.

34.

Dohm, A., and L. Shniper. 2007. Occupational employment

projections to 2016. Monthly Labor Review.Washington,

DC: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics.

35.

Duncan, A. 2010 (July). The quiet revolution: Secretary Arne Duncan’s

remarks at the National Press Club,Washington DC, http://www.ed.gov/news/speeches/quiet-revolution-secretary-arne-duncans-remarks-national-press-club.

36.

Federal Communications Commission. 2009. Recovery

Act Broadband Initiatives.http://www.fcc.gov/recovery/broadband.

37.

Feng, M., N. T. Heffernan, and K. R. Koedinger. 2009. Addressing

the assessment challenge in an online system that tutors as it assesses. User

Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction: The Journal of Personalization Research

(UMUAI) 19 (3): 243–266.

38.

Fisch, S. M. 2004. Children’s learning from educational

television: Sesame Street and Beyond. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

39.

Fishman, B. 2007. Fostering community knowledge sharing using

ubiquitous records of practice. In Video research in the learning sciences, ed.

R. Goldman, R. D. Pea, B. Barron, and S. J. Derry, 495–506. Mahwah, NJ:

Erlbaum.

40.

Gee, J. P. 2004. Situated language and learning. New York:

Routledge.

41.

Graham, S. 2009. Students in rural schools have limited access

to advanced mathematics courses. Durham, NH: Carsey Institute, University of

New Hampshire.

41.

Graham, S. 2009. Students in rural schools have limited access

to advanced mathematics courses. Durham, NH: Carsey Institute, University of

New Hampshire.

42.

Gray, L., and L. Lewis. 2009. Educational technology in public

school districts: Fall 2008 (NCES 2010-003). Washington, DC: National Center

for Education Statistics,

43.

Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

44.

Gomez, L. M., M. G. Sherin, J. Griesdorn, and L. Finn. 2008.

Creating social relationships: The role of technology in preservice teacher

preparation. Journal of Teacher Education 59 (2): 117–131.

45.

Hodapp, T., J. Hehn, and W. Hein. 2009. Preparing high-school

physics teachers. Physics Today (February): 40–45.

46.

Ingersoll, R. M., and T. M. Smith. 2003. The wrong solution to

the teacher shortage.

47.

Educational Leadership 60 (8): 30–33.

48.

Ito, M. 2009. Hanging out, messing around, and geeking out: Kids

living and learning with new media. Cambridge: MIT Press.

49.

Jenkins, H. 2009. Confronting the challenges of participatory

culture: Media education for the 21st century. Cambridge: MIT Press.

50.

Johnson, L., A. Levine, and R. Smith. 2009. The 2009 horizon

report. Austin, TX: The New Media Consortium.

52.

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2009. Generation M2: Media in the

lives of 8- to 18-year-olds.http://www.kff.org/entmedia/upload/8010.pdf.

53.

Kay, R. J. 2006. Evaluating strategies used to incorporate

technology into preservice

54.

education: A review of the literature. Journal of Research on

Technology in Education 38 (4): 383–408.

55.

Kubitskey, B. 2006. Extended professional development for

systemic curriculum reform. Ph.D. diss., University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

56.

Kulik, J. A. 2003. Effects of using instructional technology in

elementary and secondary schools: What controlled evaluation studies say.

Arlington, VA: SRI International.http://www.sri.com/policy/csted/reports/sandt/it/Kulik_ITinK-12_Main_Report.pdf.

58.

LeDoux, J. 2000. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annual Review of

Neuroscience 23:155–184.

59.

Leu, D. J., C. K. Kinzer, J. L. Coiro, and D. W. Cammack. 2004.

Toward a theory of new literacies emerging from the Internet and other

information and communication technologies. In Theoretical models and processes

of reading, 5th ed., 1570–1613. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

60.

Lieberman, A., and D. Pointer Mace. 2010. Making practice

public: Teacher learning in the 21st century. Journal of Teacher Education 6

(1): 77–88.

61.Looi, C. K., W.

Chen, and F-K. Ng. 2010. Collaborative activities enabled by GroupScribbles

(GS): An exploratory study of learning effectiveness. Computers and Education

54 (1): 14–26.

62.

Lovett, M., O. Meyer, and C. Thille. 2008. Open Learning

Initiative: Testing the accelerated learning hypothesis in statistics. Journal

of Interactive Media in Education. http://jime.open.ac.uk/2008/14/jime-2008-14.html

63.

Maxwell, E. 2009. Personal communication to technical working

group, Aug. 9, 2009.

64.

Mazur, E. 1997. Peer instruction: A user’s manual. Upper Saddle

River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

65.

McKinsey and Company. 2009. The economic impact of the

achievement gap in America’s schools. New York: McKinsey and Company, Social

Sector Office.

66.

Minstrell, J., and P. Kraus. 2005. Guided inquiry in the science

classroom. In How people learn: History, mathematics, and science in the

classroom, ed. M. S. Donovan and J. D. Bransford, 475–12. Washington, DC:

National Academies Press.

66.

Minstrell, J., and P. Kraus. 2005. Guided inquiry in the science

classroom. In How people learn: History, mathematics, and science in the

classroom, ed. M. S. Donovan and J. D. Bransford, 475–12. Washington, DC:

National Academies Press.

67.

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). 2003. Remedial

education at degree-granting postsecondary institutions in fall 2000.

Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

68.

———. 2005. 2004 trends in academic progress: Three decades of

student performance. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

70.

———. 2007. Table 192. College enrollment and enrollment rates of

recent high school completers, by race/ethnicity: 1960 through 2006. In Digest

of education statistics: 2007. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

72.

———. 2008. Table 181. Total and current expenditures per pupil

in public elementary and secondary schools: Selected years, 1919–20 through

2005–06. In Digest of

73.

educational statistics: 2008. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Education.

75.

———. 2009. Basic reading skills and the literacy of America’s

least literate adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult

Literacy (NAAL) supplemental studies. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Education.

77.

National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education. 2008.

Measuring up 2008: The national report card on higher education. San Jose, CA:

National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education.http://measuringup2008.highereducation.org.

78.

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), Baldrige

National Quality Program. 2001. Chugach application summary. http://www.baldrige.nist.gov/PDF_files/

Chugach_Application_Summary.pdf.

80.

Academies Press.

81. ———. 2003.

Planning for two transformations in education and learning technology: Report

of a workshop. Eds. R. D. Pea, W. A. Wulf, S. W. Elliot, and M. Darling.

Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

82.

———. 2007. Taking science to school: Learning and teaching

science in grades K–8. Eds. R. A. Duschl, H. A. Schweingruber, and A. W.

Shouse. Washington DC: National Academies Press.

83.

———. 2009. Learning science in informal environments: People,

places, and pursuits. Eds. P. Bell, B. Lewenstein, A. W. Shouse, and M. A.

Feder. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

84.

National Science Board. 2010. Science and engineering indicators

2010. Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation.http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/seind10.

86.

———. 2008b. Fostering learning in the networked world: The

cyberlearning opportunity and challenge. Report of the NSF Task Force on

Cyberlearning. Arlington, VA: NSF.

87.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development).

2008. 21st century learning: Research, innovation and policy directions from

recent OECD analyses. http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/39/8/40554299.pdf.

88.

———. 2009a. Education at a glance 2009: OECD indicators. Paris:

OECD.

89.

———. 2009b. New millennium learners in higher education:

Evidence and policy implications. http://www.nml-conference.be/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/NML-in-Higher-Education.pdf.

90.

———. 2010. Education at a glance 2010: OECD indicators. Paris:

OECD.

91.Pea, R. 2007

(July). A time for collective intelligence and action: Grand challenge problems

for cyberlearning. Keynote address for the National Science Foundation

Cyberinfrastructure-TEAM Workshop.

92.

Pea, R., and E. Lazowska. 2003. A vision for LENS centers:

Learning expeditions in

93.

networked systems for 21st century learning. In Planning for two

transformations in education and learning technology. Report of the Committee

on Improving Learning with Information Technology. Eds. R. Pea, W. Wulf, S. W.

Elliot, and M. Darling. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

94.

Pellegrino, J. W., N. Chudowsky, and R. Glaser, eds. 2001.

Knowing what students know: The science and design of educational assessment.

Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

94.

Pellegrino, J. W., N. Chudowsky, and R. Glaser, eds. 2001.

Knowing what students know: The science and design of educational assessment.

Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

95.

Penuel, W. R., S. Pasnik, L. Bates, E. Townsend, L. P.

Gallagher, C. Llorente, and N.

96.

Hupert. 2009. Preschool teachers can use a media-rich curriculum

to prepare low-income children for school success: Results of a randomized

controlled trial. Newton, MA: Education Development Center and SRI

International.

97.

Perie, M., S. Marion, and B. Gong. 2009. Moving towards a

comprehensive assessment system: A framework for considering interim

assessments. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice 28 (3): 5–13.

98.

Pew Internet and American Life Project. 2007. Information

searches that solve problems.http://www.pewinternet.org/pdfs/Pew_UI_LibrariesReport.pdf.

99.

President Barack Obama. 2009 (March). Remarks by the president

to the Hispanic

100.

Chamber of Commerce on a complete and competitive American

education,

101.

Washington, DC. http://www.whitehouse.gov/the_press_office/Remarks-of-the-President-to-the-United-States-Hispanic-Chamber-of-Commerce.

102.

Preschool Curriculum Evaluation Research Consortium. 2008.

Effects of preschool curriculum programs on school readiness (NCER 2008-2009).

Washington, DC: Institute of Education Sciences.

103.

Re-Inventing Schools Coalition. n.d. http://www.reinventingschools.org.

105.

Riel, M. 1992. A functional analysis of educational

telecomputing: A case study of learning circles. Interactive Learning

Environments 2 (1): 15–29.

106.

Rose, D. H., and A. Meyer. 2002. Teaching every student in the

digital age: Universal Design for Learning. Alexandria, VA: Association for

Supervision and Curriculum Development.

107.

Rumberger, R., and S. A. Lim. 2008. Why do students drop out of

school? A review of 25 years of research. Santa Barbara, CA: California Dropout

Research Project. http://cdrp.ucsb.edu/dropouts/pubs_reports.htm#15.

108.

Shedd, J. M. 2003. History of the student credit hour. New

Directions for Higher Education 122.

109.

Silvernail, D. L., and P. J. Bluffington. 2009. Improving

mathematics performance using laptop technology: The importance of professional

development for success.

110.

Gorham, ME: Maine Education Policy Research Institute.

111.

Silvernail, D. L., and A. K. Gritter. 2007. Maine’s middle

school laptop program: Creating better writers. Gorham, ME: Maine Education

Policy Research Institute.

112.

Smith, M. S. 2009. Opening education. Science 323 (89).

113.

Squire, L. R. 2004 Memory systems of the brain: A brief history

and current perspective. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory 82:171–177.

115.

Stillwell, R. 2010. Public School Graduates and Dropouts From

the Common Core of Data: School Year 2007–08 (NCES 2010-341). National Center

for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of

Education. Washington, DC. http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2010341.

116.

Strudler, N., and D. Hearrington. 2009. Quality support for ICT

in schools. In International handbook of information technology in primary and

secondary education, ed. J. Voogt and G. Knezek, 579–596. New York: Springer.

116.

Strudler, N., and D. Hearrington. 2009. Quality support for ICT

in schools. In International handbook of information technology in primary and

secondary education, ed. J. Voogt and G. Knezek, 579–596. New York: Springer.

117.

Thakkar, R. R., M. M. Garrison, and D. A. Christakis. 2006. A

systematic review for the effects of television viewing by infants and

preschoolers, Pediatrics 118 (5): 2025–2031.

118.

Trilling, B., and C. Fadel. 2009. 21st century skills: Learning

for life in our times. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

119.

Tucci, T. 2009. Prioritizing the nation’s dropout factories.

Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education.http://www.all4ed.org/files/PrioritizingDropoutFactories.pdf.

120.

Tucker, B. 2009. Beyond the bubble: Technology and the future of

educational assessment. Washington, DC: Education Sector.

121.

Universal Service Administrative Company. 2008. Overview of the

schools and libraries program.http://www.universalservice.org/sl/about/overview-program.aspx.

122.

U.S. Congress. House of Representatives. 2008. The Higher

Education Opportunity Act of 2008. 110th Cong. 103 U.S.C. § 42.

123.

U.S. Department of Education, Family Policy Compliance Office.

2010 (May 5). Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA). http://www2.ed.gov/policy/gen/guid/fpco/ferpa/index.html.

124.

U.S. Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation,

and Policy Development. 2010. Use of education data at the local level: From

accountability to instructional improvement. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Education.

125.

Vedder, R. 2004. Going broke by degree: Why college costs too

much. Washington, DC: AEI Press.

127.

Villegas, A. M., and T. Lucas. 2002. Preparing culturally

responsive teachers. Journal of Teacher Education 53 (1): 20–32.

128.

Warschauer, M., and T. Matuchniak. 2010. New technology and

digital worlds: Analyzing evidence of equity, access, use, and outcomes. Review

of Research in Education 34:179–225.

129.

Weiss, J. 2010 (April 17). U.S. Department of Education’s Race

to the Top Assessment

130.

Competition. /programs/racetothetop-assessment/resources.html.

131.

Wenger, E., N. White, and J. D. Smith. 2009. Digital habitats:

Stewarding technology for communities. Portland, OR: CPsquare.

132.

Zhang, T., R. J. Mislevy, G. Haertel, H. Javitz, E. Murray, and

J. Gravel. 2010. A design pattern for a spelling assessment for students with

disabilities. Technical Report #2. Menlo Park, CA: SRI International. http://padi-se.sri.com/publications.html.

Thank you for posting such a great blog. I found your website perfect for my needs. Read About Microlearning vs Traditional Learning

ResponderEliminar